European

Contact and Settlement

Part

Two

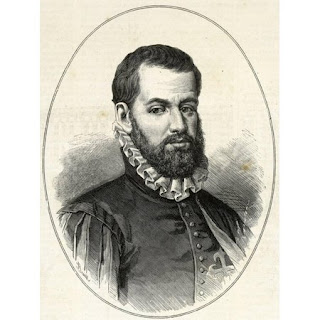

Hernando de Soto

Around 1496, or

1498, Hernando de Soto was born in Extremadura, Spain. Like Juan Ponce de Leon,

and other conquistadors, Hernando de Soto came to the Spanish West Indies in

search of military fame and wealth. De Soto came with Pedro Arias Davila, the

first Spanish governor of Panama, in 1516 at the age of 18 or 20. Here, de Soto

is given his first military command. During his conquest of Central America,

like other conquistadors, de Soto used cruel tactics and arranged the extortion

of native villages by capturing their chiefs and holding them for ransom. De

Soto became well known for this practice. He gained fame among his men for

being a very brave, loyal, and an excellent soldier. De Soto looked up to men like

Juan Ponce de Leon and craved his kind of fame and status.

Around 1496, or

1498, Hernando de Soto was born in Extremadura, Spain. Like Juan Ponce de Leon,

and other conquistadors, Hernando de Soto came to the Spanish West Indies in

search of military fame and wealth. De Soto came with Pedro Arias Davila, the

first Spanish governor of Panama, in 1516 at the age of 18 or 20. Here, de Soto

is given his first military command. During his conquest of Central America,

like other conquistadors, de Soto used cruel tactics and arranged the extortion

of native villages by capturing their chiefs and holding them for ransom. De

Soto became well known for this practice. He gained fame among his men for

being a very brave, loyal, and an excellent soldier. De Soto looked up to men like

Juan Ponce de Leon and craved his kind of fame and status.

In Leon,

Nicaragua, Hernando de Soto was appointed a regidor,

or council member. He led an expedition up the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula

in 1530 searching for a passage to the Pacific Ocean, which he discovered did

not exist. After that failure, de Soto left Nicaragua and joined Francisco

Pizzaro’s conquest of Peru in 1532, becoming his second in command. De Soto

captured Chief Atahualpa of Peru, and held him hostage. Atahualpa’s people

filled an entire room full of gold and other treasures in hopes of securing

Atahualpa’s release. The Spanish began to hear rumors about a new Incan army

coming towards Cajamarca, located in the northern highlands

of Peru. De Soto, with an army of 200 was sent to investigate.

While de Soto

was away, Chief Atahualpa was killed by the Spaniards. When de Soto returned having

never discovered the rumored Incan army, Francisco Pizzaro decided he wanted to

conquer the Incan capital of Cuzco. In 1533, his army marched towards the

capital. When they got close, Hernando de Soto and about forty soldiers went in

advance of the main army. They managed to take the city before the rest of the

army arrived. The Spaniards began searching through the town, stealing whatever

valuables they could. This made Hernando de Soto a very rich man.

By 1534 Hernando

de Soto had grown in fame, wealth, and power and was serving as Lieutenant

Governor of the newly conquered city of Cuzco. In 1535, de Soto decided it was

time to return to Spain, so he packed up all his wealth and belongings and

returned to his homeland. He arrived in Spain in 1536, a very rich man. He was

given privileges and honors, such as the right to conquer Florida, and the

governorship of Cuba. Cabeza de Vaca, one of the four survivors of the doomed

Narvaez expedition, had just returned to Spain from his horrible journey and de

Soto was fascinated by his stories. The new governor of Cuba expected to

conquer, and colonize Florida within four years.

Hernando de Soto

rounded up 620 volunteers for his expedition to Florida, and they set sail for

Havana, Cuba. The expedition sailed for Florida from Havana on May 18, 1539 on

nine ships carrying 600 soldiers, twelve priests, two women, several slaves,

223 horses, mules, war hounds, and a herd of hogs. The priests were there

because de Soto intended on converting the natives to Catholicism. Learning

from Cabeza de Vaca’s recount of the Narvaez expedition and the mistakes Narvaez

made that doomed his men, de Soto came better prepared. It is widely believed

that Hernando de Soto’s point of landing in Florida was near the present-day

Tampa Bay area. The fleet landed on May 30, 1539 and de Soto named the bay Espiritu

Santo, or Holy Spirit. Soon after the Spaniards landed, a patrol of soldiers discovered

a small group of natives. To the Spaniard’s astonishment, one of them was a

white man.

Juan Ortiz had

been living with the natives since he was captured in 1529 while helping to search

for Narvaez and his doomed expedition. After being spared from becoming cooked

alive, he was adopted by the natives, and overtime could barely speak Spanish

anymore. In 1539, when the de Soto expedition arrived in Florida, Chief Mococo

told Ortiz that he may return to his people. Ortiz, accompanied by a few of his

friends, set out to find his fellow Spaniards. Suddenly, they were attacked by a

group Spanish soldiers. Ortiz managed to remember some Spanish and shouted out

in his native tongue. The startled Spaniards halted their attack, and took the

young Ortiz to see de Soto.

After

living with the Timucuan people for over a decade, Juan Ortiz knew the language

well, and after conversing in his native tongue for the first time in a decade,

it all began to come back to him. Ortiz then served de Soto as an interpreter

on their journey through the Florida wilderness. The explorers stayed

relatively close to the coast line for over a month, until July 15, 1539, when

de Soto decided to march into the interior. Again, learning from Narvaez’s

mistakes, de Soto told his ships to stay anchored at Espiritu Santo, and await

word from a messenger as to where to go next. De Soto was seeking gold, but he

was not finding any. When asked about the shiny metal, many natives pointed

north and said something that sounded like “Apalache.” They were most likely

referring to the Appalachian Mountains where there actually was gold. Because of

this Hernando de Soto decided to head north.

After

living with the Timucuan people for over a decade, Juan Ortiz knew the language

well, and after conversing in his native tongue for the first time in a decade,

it all began to come back to him. Ortiz then served de Soto as an interpreter

on their journey through the Florida wilderness. The explorers stayed

relatively close to the coast line for over a month, until July 15, 1539, when

de Soto decided to march into the interior. Again, learning from Narvaez’s

mistakes, de Soto told his ships to stay anchored at Espiritu Santo, and await

word from a messenger as to where to go next. De Soto was seeking gold, but he

was not finding any. When asked about the shiny metal, many natives pointed

north and said something that sounded like “Apalache.” They were most likely

referring to the Appalachian Mountains where there actually was gold. Because of

this Hernando de Soto decided to head north.

The

Apalachee territory was the land between the Aucilla River and the Apalachicola

River, and after hearing reports of the gold he would find there de Soto set

his sights towards that land. As de Soto’s force moved toward Apalachee, other

native peoples close to the area warned de Soto that the fierce Apalachee

“would shoot them with arrows, quarter, burn, and destroy them.”[1]

Because the Narvaez expedition had been there a decade before, the Apalachee

were aware of the Spanish, and were hostile towards them. Hernando de Soto is

not known for his kindness towards the native peoples he encountered, in fact,

he went against his King’s orders to treat the natives well and convert them to

Catholicism. Instead, de Soto enslaved, mutilated, and executed many natives.

After Hernando

de Soto’s army crossed the Aucilla River they were in Apalachee territory. They

continued inland until they came to a great village that they found abandoned. The

Apalachee had left the town in anticipation of the Spaniards arrival. The town

was called Anhaica (ann-hi-ka), and was the Apalachee capitol located in

present-day Tallahassee not far from the capitol. Anhaica had numerous feed

stores with an abundance of food and many empty dwellings. The winter of

1539-1540 was closing in so de Soto decided Anhaica would be his winter

encampment. The army spent around six months in Anhaica, and it is believed

that the first Christmas in the present-day United States was celebrated there.

|

| First Christmas |

Pedro Menendez de Aviles

After a failed

attempt to set up a mission, and Tristan de Luna’s failed colony of Puerto de

Santa Maria, near present-day Pensacola Bay, the French began to try to

colonize Spanish Florida. In 1562, French Protestant Huguenot Admiral Gaspard

de Coligny, directed Jean Ribault to lead an expedition to the “new world” and

establish a French Huguenot colony. With a fleet of around 150 potential colonists,

Ribault left France for Florida on February 18, 1562. The fleet landed at the

mouth of the St. Johns River, present-day Jacksonville, on May 1, 1562. Jean

Ribault named the river May, after the month of their landing. Ribault then

erected a stone column, naming the territory for France. This was a bold action,

considering that by 1562 the Spanish had claim to Florida for over fifty years.

Ribault

sailed north from there, and eventually established a colony on present-day

Parris Island, South Carolina, called Charlesfort, in the honor of the French

King, Charles IX. Jean Ribault soon decided to return to France for fresh

supplies and left 27 men stationed at Charlesfort. Upon arriving back in France

in July of 1562, Ribault found himself in the middle of the French War of

Religion that started between the Catholics and the Protestant Huguenots. Soon,

Ribault was arrested, and locked up in the Tower of London.

The

French religious war was over by 1563, and Admiral Coligny had time to

concentrate on Florida again. While Ribault was imprisoned in England, Rene

Goulaine de Laudonnière was sent as his replacement to Charlesfort, which had

fallen into desolation. Laudonnière decided to establish a new colony on the

banks of the St. Johns River, present-day Jacksonville. They named the new

colony Fort Caroline on June 22, 1564. The colony sustained itself for the next

year, but then began to fall into desolation as well. The English slave trader

John Hawkins arrived at Fort Caroline and offered to take the French colonists

back to France, but Laudonnière refused.

In

1565, the Spanish were fed up with the French encroaching on their territory. The

Spanish king wanted Fort Caroline destroyed as well as the protestant French “heretics.”

The crown approached Pedro Menéndez de Aviles, commander of the Spanish

Treasure Fleet, and ordered him to organize an expedition to Florida with the

authority to settle and govern it, but first he had to rid Florida of the

French. Where Juan Ponce de Leon, Panfilo de Narvaez, Hernando de Soto, and Tristan

de Luna failed, Pedro Menéndez de Aviles succeeded. The new governor of Florida

was in a race to beat Jean Ribault to Fort Caroline, who had organized a fleet

of 800 settlers on five ships. The two fleets met each other off the coast of Florida,

and had an indecisive skirmish.

Menendez ordered

his ships to head southward where they disembarked on August 28, 1565, the

feast day of St. Augustine of Hippo. There, they built a presidio, which is a fortified base established to protect the

settlers from hostile natives, pirates, and colonists from enemy nations, such

as France and England. They named the settlement San Augustin, present-day St. Augustine, and built up earthworks to

further protect themselves. An attack from the French at Fort Caroline seemed

imminent and on September 10, 1565 Jean Ribault took his fleet south with the

majority of his men towards St. Augustine to pursue Menendez. Hearing of

Ribault’s movements, Menendez sent soldiers on foot forty miles north to Fort

Caroline during a terrible hurricane. The storm tossed Ribault’s fleet around,

and the French wrecked south of St. Augustine near present-day Daytona Beach.

The surviving crew, including Jean Ribault, wandered north to present-day

Matanzas Inlet, about fourteen miles south of the Spanish at St. Augustine.

Back at Fort

Caroline, the Spanish attached during the hurricane and easily defeated the

small garrison of French soldiers left behind. There were about twenty soldiers

with a hundred colonists inside the fortification and the Spanish slaughtered

nearly all of them, only sparring around sixty women and children. The Catholic

Spaniards hung the dead bodies of the protestant French in trees with a sign

reading “Hanged, not as Frenchmen, but as heretics”. Menendez decided to rename

Fort Caroline, and called it San Mateo. There Menendez left a detachment of

men, and headed back to St. Augustine. Soon after his return to St. Augustine,

Menendez was informed that the French had shipwrecked and were only fourteen

miles south of them. Before Governor Menendez could really work on building a

permanent settlement, he must first destroy the French presence in Florida.

The marooned

French sailors were soon tracked down by the Spanish, and rounded up. Jean

Ribault thought he was going to be treated humanely, so he surrendered without

a fight. He was dead wrong. By order of the King of Spain, the Spaniards gave

the protestant French a chance accept Catholicism. Those who did not convert to

Catholicism were taken behind a sand dune and hacked to death with a sword.

Only a handful of the French were converted, and around 350 men, including Jean

Ribault himself were massacred. The location of this event still bears the name

“Matanzas”, Spanish for “massacre.” As horrific as it was, still, Governor

Menendez carried out his order to dispel the French from Florida, and with the

entire coast back under Spanish control, he turned his attention the King’s

other orders, which were to build a permanent colony and establish a mission system

for the natives. The Governor invited Jesuit priests to St. Augustine to start

ministering to the locals. Menendez anticipated St. Augustine, and Florida

altogether, to prove lucrative to himself and the King.[2]

Sources used:

The New History of Florida (pp. 40-61). Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Lyon, E. (1996). Settlement and Survival. In M. Gannon,

Hann, J. H. (1988). Apalachee: The Land Between the Rivers. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

No comments:

Post a Comment